It probably all started when Jack's prostitute told him she was pregnant. Or maybe it started because Amelie got pregnant and then Jack wanted his prostitute pregnant. But it started innocently, and with fecundity, which is always dangerous.

It's exactly midnight, December 12, 2011. I'm anchored off the coast of San Juan del Sur, Nicaragua. My wife and son are sleeping downstairs. One of them is snoring. I'm wide awake, pouring sweat, sitting in the boat's cockpit with Jamie, who is giving me a tattoo by headlamp, and Devin, who is deliriously giggling and strumming his guitar. The tattoo is a compass rose, one of those designs you find on a compass.

A hot night wind flows around the boat, roasting us. None of us have shirts on and I feel a bead of sweat run down my side. For dinner we had roasted chicken, a local rum called “Joyita” (or “Little Joy”), and cigarettes. We finished the chicken hours ago and are most of the way through the rum, coke, and smokes. I look up and exhale. Jamie pokes another needle into my elbow, traditional tattoo technique, it stings enough for a kick of adrenaline that calms. Mouth open, smoke rising, I watch the stars waltz around the mast.

This land of Sandinistans, surfers, narcotrafficantes, prostitutes, politicians, goddam howler monkeys, and crazy, swinging stars has proven to be a fog bank of cultural confusion and political mayhem. It's also become home partly because my son was born here. We've been here two years now and in those 22 months the moral fogbank has thickened to quicksand. The murk of coffee-swilling gringos, improverished Nicas, warm-hearted fishermen, lawless pirates, and a traditional neighborhood stitched together by the reputation of its members, has come to almost paralyze me. I was living in a different, very Latin American, world. I had lost a true north. My moral compass had cracked.

So had the rest of the town.

PART ONE: THE NEIGHBORHOOD.

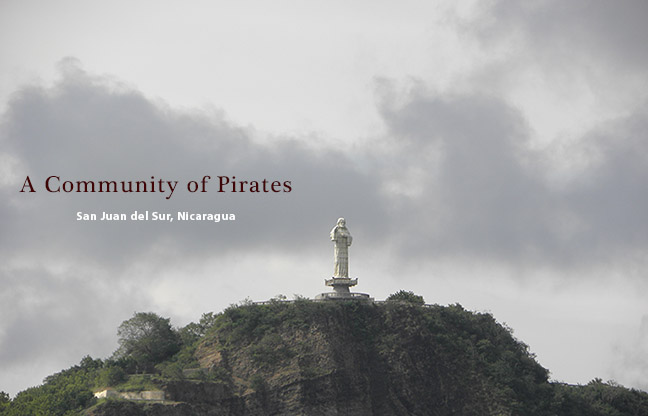

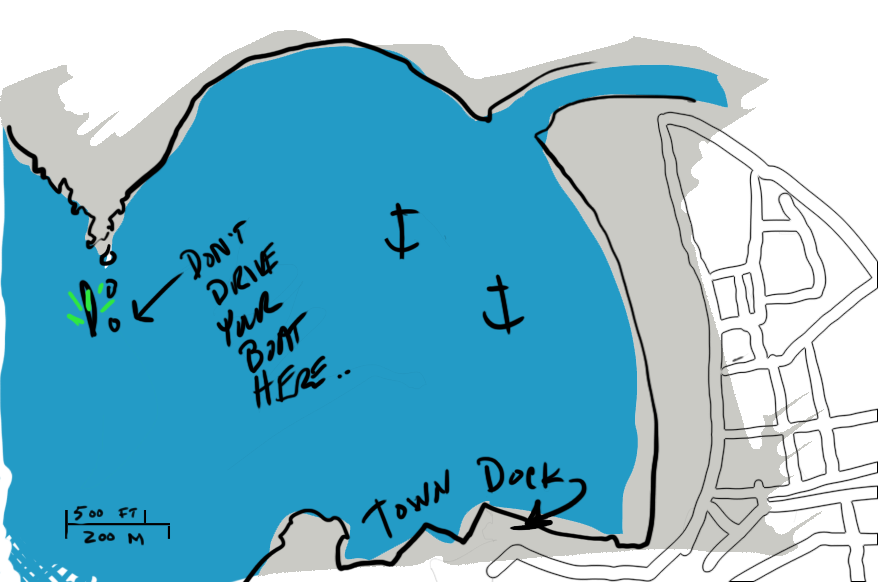

San Juan del Sur sits next to a lovely crescent of a bay framed in by massive orange cliffs. The cliffs are spattered with jungle green. To the north of the bay is a reef of rocks that reaches out from that cliff. We anchored outside the river mouth in about 30 feet of water, under the big statue of San Juan, who looks down on everybody with his arms out in a kind of aggressive-passive manner. I guess he's some ancient surveillance system, a big ghost that reads minds, but this statue of San Juan sees all. He sees the tourists, the surfers, the robbers, the drug dealers, the lovers, the coconut salesman, the sole town hooker, the hundreds of churchgoers that daily enter the little brightly-colored church in the middle of town, the milk salesman that whips his dear old horse, the over-priced bread shop and the smiling bakers that sweat there, the under-priced carpenter's shop with same, the vigerone saleswoman, the veteran, the homeless man, who is missing his leg and dresses in dirty army fatigues, the young skinny Salvadorean couple who are trying to start a pupuseria, the old woman who always, always asked me how my mother was, the old man who always, always, wanted to cut my hair, his wife who scolded me for not wearing a shirt, and my wife, and our son, and I. We all gathered in San Juan, under that statue, and lived there together for two years.

Each morning my wife and I would take the water taxi to land. This meant that we got to know every fisherman in town, every cuidador, every mechanic, every captain, every random kid with nothing to do other than jump off the dock all day. All the greatest town gossip happened each day in that taxi.

The statue saw all we did and knew and was witness to our loves and sins. There was old Juan Paisano, a seasoned Nicaraguan boatwright who looked like a tan lawn gnome. Señor Paisano has built 23 wood boats in his 80 years. He still pulls a saw today and has more energy than a cockroach wired to a nine volt battery. There was Stu, the Australian Guitarist, a man over two meters tall, a handsome and elegant fellow, who can sing as lovely as most of the birds that live in the valley with him. He makes a living selling surfboards, coding mining spreadsheets, singing songs, and hosting parties. There was Francis, the local laundry girl that has a smile so bright I'd go do laundry there just to blink at her, in awe, like blinking into the sun. She worked with her mom, and her grandmother, and they always had local gossip to giggle over. There was Captain Zetada, an American sailor and ex-Navy SEAL, who broke his back in Baghdad, during the war, and then sailed to San Juan to make a bigger boat, live with his wife and daughter, and spend his days selling soap, coconut oil, chocolate and other sweet gop he sells from his wife's massage parlour (he's really restoring an historic boat, however). He eventually got arrested along with Li'l Jim. Li'l Jim was a slimy, bespectacled, and deceptively cute Alaskan, who didn't set his boat's anchor right when the winter storms came. His boat was beaten about the ears by the winds and waves during the entire winter and came damned close to sinking right there as we all watched from the shore. But he's a survivor, as we Americans like to say, and he escaped the storms with an intact boat. I'll come back to he and Zetada. There was Tapio, a tall drunk Finn who leaves behind him a wake of destruction. He arrived with his boat completely fucked from running it aground and twisting his rudder up into a 90º position, and shearing off the aft portion of his keel (he later hired me to fix it, which I did, with the help of 23 local fellows, and that was both a challenge for my Spanish and those obliged to listen to it). It is said his father sends him money to keep him from returning to Finland. There was the Viet Nam vet named Jack, who got his hooker pregnant (not the hooker from San Juan, but one of the many prostitutes in Managua). There was Laura, the Spanish chick who got pregnant (by her husband) and had a kid the same week my wife did, and she (Laura, I mean) ran a restaurant that served a spiced octopus so good that I made myself sick because I ate three plates in one sitting. I just ate too much octopus, as I did one Christmas, when I ate too much fudge. Anyway we got to know the butcher, the baker, the electrician. I got to meet the retarded kid that sleeps with dogs, then throws rocks at them to get his food from them, and the local coke dealer, gas station attendant, Lola that sells vegetables, Rigoberto that keeps the local engines running, Luis, that runs the boat yard, Carlos, who runs Luis, David, who runs Carlos, and the lovely Ms. Maria-Eleña, who ran all of them from behind the reception desk where she so smilingly worked. I met Maria-Eleña's mom, who worked at the local pulperia, selling groceries, and her sister, who turned me on to an ice cream sandwich named Treats. I met Antonio, a young punk who, every day, at nearly every hour, would hang out with his buddies on the dusty corner, and grin, and laugh with me, and could say one phrase in English, and that was “Chillin' like a Villain.” He liked LMFAO and Snoop Dogg, so I guess he learned this delicate phrase from them. Eventually Antonio hooked up with an older Gringa, a wealthy gal at least twice his age, and he drank so much we watched his face inflate in the course of less than a year. There was Umberto, the great-bellied mass of a man that hated gringos, and who finally agreed to talk with me when, after 18 months, I either knew or was friends with every other person in our town, and I had him surrounded, and finally he had to be nice to me. He had reason to hate the gringos I will never see. A little of it I did see, because gringos go to Nicaragua and exploit the idea of having someone work for them for $10/day and show their power and their wealth because they have had neither of enough in their lives. One example was Righteous Ralph, from Texas, who insisted everyone act like him, and who, after living there for a decade, and having butter on his toast every morning, still hadn't bothered to learn the Spanish word for “butter.” He was like a modern conquistador, demanding everyone speak his language, comform to his ways, protect his identity, and serve. His workers did that, too, but they quietly told me about his faults. Anyway I also got to know his polar opposite, Jane, who also owns a hotel, but does it with the sincere grace and the spirit of a saint. She has opened a few libraries in Nicaragua, and her ongoing goodwill is matched only by the happiness of the people that work near her. I met her through a man I will call John the Wise who became a good friend, a geeky Yanky that knows, after living in Nicaragua most of this life, how things really, truly work. I learned a great deal from him about Latin American politics and society, and I'm thankful, like someone that has been taught how to fix a motor There was Joseph The Austrian (who my wife wrote about) always accompanied by his parrot and a cigar. There was also Freddy and Oscar and Felix the security guards that kept an eye on the docks, Ché, the water taxi, Mario, his dad, and perhaps a hundred other people I met in that village under that statue, each with beautiful and heart-rending stories of their own.

We talked often, all of us, and for me much of this had to do with my son.

Having a baby in Nicaragua makes everyone want to come talk to you. Each day, or nearly, these friends, and others, would come up to say hello and ask how my family was doing. Going to the store, to buy a simple six-pack of beer, became a gauntlet to run.

“Hey Marco del Barco! How's your family!? How's your son!?”

What can one say in the face of such? It is one thing if people nod, or say hello to you. You nod, say hello, and walk by. Germans, English, and Americans, these Protestant peoples I have noticed, like to nod, turn down the mouth, and frown at one another as if they are commiserating. It is another if people ask how you are. Then you just say good and walk on. But this crawling into my soup and demanding information about my family. It is so kind and unfamiliar I reacted as if it were rude, by accident, and reminded myself to appreciate the warmth.

“Oh, great, thanks for asking. Good; eating, shitting, drinking, and sleeping. Baby stuff you know. . .” and I would start to step away.

“Good good! And how is your wife?!”

I guess there must be a high rate of infant mortality because I would see the same person five or six times a week and they would ask me these same questions as many times – more, even. They might ask if we needed anything, which we never did, luckily. So I got to spend time in this neighborhood. It's a headache and takes time. It offers great social security. I got to see what it's like to live in a “community.”

My wife, who has lived in Africa for some time, tells me the same thing happens there. It is not polite to simply say hello to someone passing on the street. These questions must be asked if one has been properly raised. It's only polite. It's only civilized.

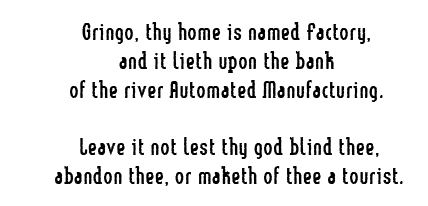

What is it that 'developed' countries are developing? It ain't civilization. In the 1970s Ivan Illich, an Austrian philosopher, calculated that if you add up how long it takes to earn the money to buy a car, the time it takes to earn money for fuel, the time you spend in a hospital because of that car, the time you spend fixing it, and the time you spend making money to pay to fix it, the actual speed of a car is about the speed of walking, a little over 3 miles per hour. You can do the same studies on computers and get the same kind of results, but that's what Ivan did on cars. So this means that industrialization hasn't produced a vehicle, but a system by which my kind neighbors, in a place like Los Angeles, or Phoenix, or any other great automated grid, can no longer harass me with bothersome questions. Ivan says it's counterproductivity, but I think developed countries are producing insulation. Insulation from neighbors, from distance, from cold and heat and all else that is inconvenient. So developed countries will continue to develop whatever they are developing. I fear the exports. So much for that.

As I would walk through San Juan not just friends but total strangers would come up to me on the street and ask how my kid was doing. These people were friends with his Babysitter, Annabelle. He was a goddam celebrity. Walking to the market became a maze-garden built out of smiling questioning faces, outstretched hands, and new spanish words like Barron and Chiquitito and Chavalito and Bandito and all them things I had to deal with, just so I could pick up a six-pack of beer, a pack of smokes, and some diapers. I went out less often, and when I did I left armed with some prepared comment like, “He puked on himself today, thanks for asking!” or “He pissed on me three times! Here! Hold him!” thinking it would buy me some space, but it never did; my neighbors and friends would be happy to be peed on by The Urinator, and they would bounce him around and smile meanwhile asking what mom was eating and making dietary suggestions (colic is a great frontier of human ignorance) and pretend to help the kid stop puking. I soon stopped such antics in the face of sincere kindness.

All I wanted to do was get back to work, to get back to being productive, to return to my illustrations and software and writing. But there I was, holding a smiling baby, surrounded by smiling friends, awkwardly stitched into a friendly, loving neighborhood for, perhaps, the first time in my life.

I tasted authentic community and it was, I must admit, a bit sweet for my taste.

One day, walking down the street, uninsulated, if you will, I thought to myself, “If I had a fucking cordoba for every time someone said hello I'd buy Nicaragua.” I didn't know it, but, in fact, that was what was happening. I was walking in a labyrinth of love, a kind of framework of affection. And like all wealth, it was inconvenient.

In this cacophony of voices and faces, in this great sweating swamp of friends, there were three monstrous men that loomed large on my horizon. They became, for me, the compass, the deviation, and the variation by which I found this true north of ideals that I mention above. One was Jack, another was Captain Zetada, the other was Li'l Jim.

First, for all I know Jack is now dead. But it started with his prostitute, Maria.

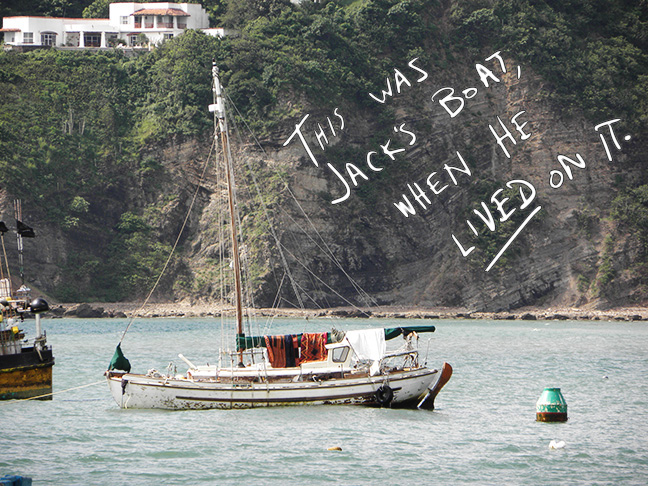

Jack lived, before all this piracy shit went down, on a little wooden boat named Mandan. Jack was a bear of a man, unshaven, stained clothes, meaty hands, sweaty face, and white hair that sprouted out of his balding pate. He was as kind and as fun-loving as a puppy. He was always up for a laugh and would was the kind of man to do a small jig, and laugh, then stop and put his hand on his lower back. His body was betraying his spirit. He had lived in San Juan del Sur for years, though I cannot say how many. He was a classic, tough Old Salt and had spent the last winter in the bay, as well, when all the other boats, ours included, had hauled out to avoid the winter storms. Jack used to fly helicopters in VietNam, worked as an oil grunt for Haliburton, and came from Billings, Montana, or something. When we met him, however, he was done with all of that and he and his cat lived on Mandan.

About 65 years old, he was American vintage. He smelled of rum and cinnamon, and his bad back forced him to talk bent over, hands on his knees, looking up at you, despite being such a large ox of a fellow.

He would head in to Managua once every week or two to go visit a whorehouse up there and, like all the other neighbors and friends, when he wasn't doing that he was busy pestering Amélie and I. Especially when she was pregnant.

“Is she eating enough? She looks skinny. Her arms look too skinny, Marco. You oughtta stop feeding her fish and give her more beef.”

Or when I was painting the bottom of the boat and she had to spend an hour inside.

“That shit's toxic, full of lead, and your baby's gonna be born retarded if you let her sit in there. C'mon, Marco, what the hell are ya thinkin?” and then he'd slap me on the back and I know he meant, always, very well.

This went on for months and in that time Jack and I got to be pretty good friends. I mean, that's the kind of thing a real friend says, right? We'd stand around the boat yard, hands in our pockets, and slap a hull of a sailboat that had just been hauled out, or we'd kick at the dirt as Jack would explain politics, or wars or the industry named Big Oil, or what it meant to live in the States, then he'd eventually get around to telling me how I should be taking better care of Amélie and why she oughtta have a hamburger. And that was always a prelude for him talking about how he'd always wanted to be a father.

One day he unloaded it on me.

“I've got a secret, and I don't want you tellin' no one, ok? You got it?”

I solemnly nodded.

“I'm gonna be a daddy,” he whispered.

“What?” (I couldn't believe he said the word “daddy”) “Did you adopt or something?”

“No, I got Maria pregnant.”

“Jack.” I looked at him not quite getting this. “She's your prostitute.”

Jack started giggling like some big fat kid that's just figured out how to torrent XBox games.

Some people think prostitutes are paid for fucking, but this is not the case. They are paid for not having emotional hangups. Or kids. And this transgressed upon both of these unwritten rules of prostitution.

“I know! She's so knocked up she's spending the mornings puking!”

He giggled again and I put my face in my palm.

“Don't worry – we'll do a blood test and all that normal stuff to make sure the kid's mine.”

Normal stuff. There is no such thing in this world.

“What makes you think it's yours?” I asked.

He looked at me and said, in this soft, completely convincing tone, “She told me I was the only one she'd had unprotected sex with.”

Several months went by and I saw little of Jack. He had told me that he would set up camp near Masaya, up near Managua, and raise his kid and some pigs. Sounded like a good idea to me. Then, one day, he came back to San Juan to help me rebuild a boat that had run aground. We needed a new prop shaft cut, so we had to go to Rivas. On our way Jack caught me up on his plan.

“Maria's great. She's big and plump like dumplin'.”

“So health is good and all?” I asked.

“Yeah. You know the best of it? She cooks me meals, and puts my meals down on the table, and then stands back and waits while I eat.”

That didn't sound to me like the best of it, but I've never gotten a prostitute pregnant, so I didn't really have much to say in response. It didn't sound like an entirely healthy situation, but then again, what do I know?

“The kid's due in two months.”

Those months came and went. One afternoon I was standing on-deck of the Goose and noticed that Jack's boat, Mandan, was left alone to gather barnacles and grass, and Jack had already drug the solar panels and other electronics useful for his home up into the jungle. It was at that minute that Jack finally called me from the delivery room. He was so excited, more than I had ever heard him. The hospital in Managua, The Metropolitan, is a great hospital. I've had a doctor's secretary call to tell me the doctor will be 15 minutes late, and I've never seen such advanced medical equipment, so I was sure the delivery went fine.

“It's a baby girl!” he squealed, “I'm a daddy!”

Two months later, this time in a little restaurant on the beach, the sun setting, two Toñas on the table, and Jack is not quite so gleeful. We smoke cheap cigarettes and watch the people walking on the beach. Jack's silent for a bit.

“The kid doesn't look like me.”

He looks up, takes a sip of beer, and says, “She's dark as a ditch, big round head, flat nose.”

“What are you gonna do?”

“Blood test.”

We talked about boats and other things.

Two months later. The phone rings. Jack tells me that Maria's brother has asked him to leave the house. I ask why and Jack tells me that they want to give the kid herbs and traditional Nica medicine rather than actually give the kid, as Jack puts it, “stuff that works.”

I walk up onto the foredeck and look at Mandan. It's morning and a small motorboat tows around one of those blow-up banana-boats, covered with screaming and bouncing kids, their arms above their heads, waiting to fall off into the water. I plug my other ear to hear better.

“. . . grass-and-mud compress with grasshoppers ground up in it. Then they put on her head. For pneumonia. What the fuck?”

I guess some sort of punch-up happened, between Jack and Maria's brother, and that was either just before or just after Jack had been asked to leave the family. Jack had already abandoned Mandan, returned her to the bank, and I had found two people that were potentially interested in buying the sailboat. I asked Jack what to do about a title transfer, how to sell her. After all, it would probably be some money for him.

“Talk to the bank,” was all Jack had to say, and with that he hung up, and sent me the bank's contact info.

Mandan, still alone, seemed to be turning a hue of vomit, a yellow-green-grey, and the morning sun only shone light on the unhealth. Boats surely have spirits and Mandan's was a sad one.

PART TWO: A SUBTLE FATHERING OF PIRACY.

Remember Li'l Jim? The bespectacled cute guy from Alaska?

Well, when Li'l Jim had anchored his boat during the winter storm that year, and when it started to take on water, he asked everyone for help. For a night or two he and I spoke. He mentioned his past travels among indians in the jungles, his smuggling adventures, selling hallucinogens, how he learned Spanish, his bead-crafting, some gold prospecting he'd done, and that he had two kids in the states with a previous marriage. He was out of money, and his boat's hull – a wood hull – had been compromised by some worms that were eating through it (a common problem in the tropics). Jim also told me that he had let his American passport expire so he didn't have to pay his alimony payments (he had a reason for not paying them, a justification, which I now forget). On those rainy nights, while he ate dinner at someone's house and passed the hat, we all pitied him. It was easy to do as he had a chubby angelic face with round glasses and a weepy smile.

Ever notice how boaters wave at each other all the time? I like to imagine it is because we all think we are on a parade float, but the really it is because all of us are afraid of dying alone. If you sail you may, one day, have to ask a total stranger to save your life. So we tend to be pretty generous when its time to give a little love. Or ropes. Or fiberglass. Or money.

Everyone dug deep. Captain Zetada loaned him a couple of anchors. We loaned him a pump and some tools. Igor, the Russian, loaned him US$2000. Other people came to the rescue, spending the night helping him bail water, or loaned him more money, or helped him fix a problem with his motor, so that the intake for the cooling system could be redirected into the interior of the boat, and the water removed, and other people helped in other ways that he always promised to repay. Captain Zetada loaned him more money. Then, after the storms died down and Li'l Jim was still floating, he mentioned to Zetada his passport situation. So Captain Zetada also helped him get a passport called a “world passport” that claims you are a “citizen of the world.” They both ended up proudly walking around town with this exotic modern passport and, for a time, seemed like two good friends who were happy together, geeking out over international travel documentation. With the loans of the previous months, Li'l Jim had enough money to hire the local crane and haul his boat out of the water, and so it sat, on land, next to Zetada's boat, another wood vessel. And Jim borrowed some tripod boat stands from Ralph, to support the boat while he worked on it. Meanwhile, the kind Captain Zetada did what he could on the side to help, loaning Li'l Jim more money, repairing the broken stuff, or helping haul things up the ladder and on to the boat.

It was the money, of course, that sparked the problems between those two. Li'l Jim put that money Zetada had loaned him to use by starting a competing coconut oil business. He did quite well, and quickly, and that put Zetada out of business. And Zetada told me that he never returned the anchors nor the money, and so these things set Li'l Jim and Captain Zetada against one another and they became enemies and avoided fist fights and, therefor, seeing one another.

In the months that followed Li'l Jim, with his new coconut oil empire, seemed to have forgotten not only the debts he owed, but the humility that earned him the advance. There seemed not a person in town that was happy with Li'l Jim and there was not a Gringo I knew of that he did not owe money to. Sometimes I would see him chatting up a young woman I'd never seen before; presumably a tourista visiting town.

This was happening when Jack decided to leave Maria's.

When Jack told me that he'd abandoned Mandan (and was also abandoning the dark-as-a-ditch, round-headed, flat-nosed baby that wasn't his) I mentioned it to two people. Then, three days later, several of San Juan's sailors started eyeing Mandan as ripe plucking. There was ample talk of pirating the boat, of taking it to the south seas, of forging the paperwork that was needed since, as long as you didn't go back to the States, American paperwork, if forged, would work pretty well. Mandan, after all, was going to be sunk, looted, or stripped for lumber. There was no infrastructure to take care of the thing. There was no-one to donate it to. Not like there's a local cub scouts troop, or god club that like sailing. Maybe in Managua, or Granada, but not in San Juan. She was a perfectly good boat. She just needed someone to take care of her. Though I have my own boat I also enjoyed a vicarious giggle over this and stood on the beach, twice, hands in pockets, looking out at Mandan and discussing the pragmatics of piracy. But of course we all knew that this isn't the way one goes about things, so Mandan floated off the beach, alone.

Mandan eventually got her visitor.

One evening Li'l Jim hired a guy that worked at the local grocery store. A big puma of a jungle man, he and Li'l Jim, in the liberty of night, rowed out to Mandan, climbed aboard, and in one (some say two) night's work, stripped the rigging, bundled up the sails, prised off the hatches, pulled out the plumbing, picked apart selected deck hardware. Oh, and in an act no less complicated than heart surgery, they lifted out the motor, as well. This involves some serious work – lifting a motor out of a boat is a bit of handiwork that involves pulleys and strategy – which they did out at anchor. Then they cut the mast, chopped loose Mandan's chain, and set her adrift. The two banditos headed back to shore and cute Li'l Jim, for lack of another place to put it, left the motor next to his boat, climbed he stairs, and went to bed.

The next day Mandan was found offshore by some fisherman (she'd only gone some 10 miles). The fishermen called the coast guard, who towed the neglected and abused sloop back in and tied her to the bay's only buouy. They reported what they'd found to the Port Captain.

Now The Port Captain, Captain Flores, was a bit of an eel. He once changed a navigation light at the north of the bay, one that marked some rocks, from green to red. This might seem a small change, but it told boats coming in at night to keep that light to their starboard, or right side. When you're driving back into port the story in the Americas is that you keep the red on your right when returning to port (or “Red Right Returning” is how many American sailors remember it). Three boats ran aground on those rocks as a result of that color change and Flores collected money by helping these same boats return to sea. It was a method of making a little plata. But that is another story and I simply point to it because this act, like the rocks below the surface of the water, belied Captain Flores' personality. Plus he had a mean little pig-eyed dog.

This surly, pregnant bastard of a man that played devious political games and followed the exact stereotype of a Latin American dictator, down to the moustache, did, to his credit, keep close track of the boats in the bay. And when Mandan was towed back in he looked into it.

The following morning Flores approached Li'l Jim and asked how the motor, sitting on the ground in front of them, had come to be in such a place. According to the gossip I heard in the daily water taxi, Li'l Jim said he had removed the motor himself and had papers for such, and so Flores asked to see them. (As far as I know the only person Jack was in correspondence with about Mandan was me.)

When no such papers were produced Flores asked Li'l Jim for his passport. The “World Passport” didn't appeal to Flores as it did to Captain Zetada, so Li'l Jim was handcuffed and immigration was called. Immigration asked him how he came to get such a passport and Li'l Jim pointed to Zetada. Zetada was then also handcuffed, and the two were promptly tossed into the clink in Managua. The passport, declaring them “citizens of the world” allowed them to be treated as any citizen of the world in any country can be treated; imprisoned.

PART THREE: LI'L JIM'S INFECTION.

So let us take a fast tally of our little Community.

Li'l Jim (who had his enemies, thanks to his infectious personality) was in prison, his boat was on the hard, and he was up to his tits in debt. Zetada (who had his family and friends, also thanks to his infectious personality), was in prison, his boat was also on the hard, and he was mad as a wet cat. Jack had disappeared into the Jungle. Flores was sitting on at least two boats that he could either sell or strip and who knows what kind of kick-back the Sandinistan Immigration would send his way. The dozen sailors that were owed money watched this play out, growled, and cursed the day they met Li'l Jim (let me count them: Righteous Ralph, Julian, Cocaine Ken, Captain Zetada, Zetada's wife and daughter, Igor and his wife, taxi driver Che, his dad Mario, Joseph the Austrian, John the Wise, Tapio, and probably as many young tourist chicas that had fallen into Li'l Jim's greasy bedsheets). And as for myself, my place to relax my mind had turned into a cauldron of contempt. But, compared to Mexico, there was less accordion circus music.

After two years in Nicaragua we had decided to leave. Mostly, I had a window in which my work schedule would be dropping, the winds would be good for a trip south, we had seen what we wanted, had made Nicaragua a part of our story by having a kid there, we wanted to see more of the earth, and this piracy thing was getting weird enough that it finally shut the chapter. We got back from a short trip to the States and set about preparing to leave.

Then we discovered that we weren't allowed to: the state had put an embargo on all sailboats.

What happened next did not relax my mind, and we may continue to play accordion circus music in the background at an increased speed. Let us also speed events up in what seemed a kind of acceleration of this Community's collective unconscious. Li'l Jim sparked something. First he had robbed from the people around him, then he had looted Jack's boat, and then Flores sent the sailor up the river. This then set off a wave of piracies around the bay of San Juan del Sur. There was, that same week, a fishing boat that was robbed (a very rare event), two tourists were mugged, Cocaine Ken got stabbed in the pecker, and a dinghy got knifed, leaving a deflated pile of rubber at the dock. It was, I understood (again from the taxi rides), a revenge murder.

Finally, those sailors that were waiting for Li'l Jim to pay him back got angry enough that at least one of them broke into Li'l Jim's boat. They just climbed up the ladder and crawled into the boat. This was done right under the noses of the coast guard, the dock guards, and the Nicaraguan navy, all of whom used that same dock. A bag landed in Igor's cockpit, full of electronics, as a kind of robin-hood recompense for the $2k that Jim owed him. Other stuff was distributed as well. On our boat appeared a bucket, a rope, and a fender. The thieves redistributed what little wealth Li'l Jim needed to get out of prison.

Then, a couple weeks later, and the week of our departure, the security guards told me that Li'l Jim had finally gotten out of prison. He got back, visited his boat, found out it had been robbed, and promptly filed a police report. The security guards laughed as they told me that the police were laughing, as well. And as word spread none of the sailors seemed to feel much remorse for Li'l Jim. The pirate had been pirated.

Though the piracy seemed to be getting a little heavy we'd not yet seen the fattest of it.

The following week – the week we had decided to go – was the week we learned of the embargo. It was the Sandinstan government's enforcement of a new law. The state said, “Boats need to be registered.” Let's stop there. “Boats need to be registered” is the nautical equivalent of “Cars need to have license plates.” This is a bright indication of a state of lawlessness. The FSLN (the Sandinistan government, or “Federal Sandinistan Liberation Front”) had never really gotten around to setting up a boat registry policy, at least not on the west coast, and they also determined that if a boat wasn't registered then there would be a fine. That seems fine to me, because one must enforce one's law. But, in classic Sandinistan style, they also determined that, since the law had been passed three months ago, and they hadn't gotten around to telling anyone, that fines would be retroactive. That was not fine. That, too, was lawlessness.

To make matters more absurd, the coastal commission and tax bureaucrats then decided that they would charge all sailboats $454 per month to anchor in the bay. A strange price to pay since we were not provided with electricity, guards, water, bathrooms, showers, or even a dock to tie up to, services that are usually offered in marinas around the world with the same price. Hell, at Raffles marina, in Singapore, you pay the same price and get a swimming pool, a bar, a bowling alley, and other goodies. So I never really figured out what the Sandinistans wanted us to pay for. It turned out to be illegal, according to international maritime law, but they decided to squeeze us until we squeaked, just because they could.

And that is how the pirates that pirated the pirate got pirated.

That was kinda the end of the Community feel-good vibe.

PART FOUR: THERE GOES THE NEIGHBORHOOD.

From the FSLN's perspective it might have seemed a pretty good way to pick up a fast $30 or $40k. But the attitude may be traced to Costa Rica, and to Los Suenos (in Herradura Bay) in particular. These ricachones have found a means to charge absurdly high rates for the fat-cat fishing yachts that spend $12,000 on gas per day. Los Suenos is one of the most horrific wastes of money I have ever seen (and I am counting racetracks in Abu Dabi, palaces in Mumbai, and resorts in Fiji). Costa Rica, or her tourists, or both has created an inflated economy and a severe class division that makes Nicaraguan pen-pushers and bean-counters slobber with envy. The Nicaraguan neighbors evidently heard that Los Suenos was charging stupid prices, and the Nicaraguans, with a typical farmer philosophy of “I can do what my neighbor can,” did what any pirate does; they broke rank.

But I think Li'l Jim and Jack had more to do with it all. The state was just responding to the weird gringos on boats. The timing of the events is too tight for me to overlook the cause-and-effect fallout. Jack's boat is abandoned. There's a claim that a law is needed. It gets passed but not ratified (or something – I have no clue how Sandinistan politicians think). Then, a couple months later the boat's pirated and all hell breaks out. Their law gets ratified, but the gringos of San Juan are causing such problems that the government looks for an easy way to both pass a law and take their money. Solution? An embargo.

Thus my dear wife and I went to the Taxes offices, then the Import offices, then the coastal commission offices, foisting our baby along in front of us at each stop as a kind of social snow-plow (which, in Latin America is a perfectly acceptable negotiation tactic). Fortunately, thanks to our Nicaraguan kid, control of the Spanish language, and the fact we had decided to leave, we side-stepped the state's swipe of bureaucratic piracy, suffering a scratch of merely $1000. The boats of Li'l Jim, Jack and Zetada all went to the Sandinistans. The money of the rest of us went that way, as well.

The piracy in San Juan started small, grew fast, and happened in a cumulative series of social fissures, or separations. The separations that had been Jack's retreat into the jungle, Jim and Zetada's imprisonment, Flores' jefe role, and the state's attempt at building class divisions like Los Suenos. With each separation it caused a cracking apart of Community. Pirates make shitty neighbors.

In the end a community is just an arbitrary set of moral rules (written or, in most cases, not). Those rules or morality are guarded, groomed, and enforced by the members of the community because each member has a reputation to protect. The reputations create glue, and a method of punishment, and if one man breaks from that cast, and there is no enforcement, then piracy reigns.

Jamie pricks me with the tattoo needle and I put my forehead against the compass housing. It is cold and my forehead is sweating. I open my eyes and the compass light is orange, noting each of the lovely three hundred and sixty options, like cards in a tarot deck, or demons that may be summoned simply by turning the magic wheel. The compass tells all at once.

But its hard to follow.

Magnetic north moves each year. The magnetic pole that draws the compass' needle creeps around under Canada slowly enough that we think we know where it is. But then a few years go by and our North has become an East. Magnetic north, like some invisible god, drunk and staggering around up north, has his own way of doing things. Sailors have known about this for a long time and we call it “variation.” It's the movement of true north.

Meanwhile, the boat's compass is also affected by electronics. All magnetics are sensitive and all of them are pulled one way or another by some small electrical field, or a magnet, or even a body of water. Sailors call this “deviation.” It's the effect of other forces.

So to find true north, the north we all must use, one must take magnetic north and do some simple math to correct for it. You have to account for your local deviation and the variation in your boat.

The rules of morality are like this. A community's morality moves slowly and if you navigate by only that, and assume it's right, and don't do the math to correct for it, you'll get lost (if not imprisoned). In Latin America morality is determined by the customs. Customs count more than the law. In the United States morality is determined by the law. Laws count more than the customs. The math is simple, but the navigation is not and we must take into account where we are when we navigate. That true north, the morality of the region, is always different.

Of course any point of the compass, like 360 ideals, can offer a clear line along which to sail. And in life, as on the sea, we pick our ideals and then steer that way. And though the points of the compass may be dependable, even our ideals are subject to deviations, variations, an occasional cracked glass, magnetic flux, a drunken decision, or bad math.

Jamie pricks me again on my elbow and I lift my head from the binnacle.

It probably started with one of those two pregnancies, and ended in government legislation, but the descent into Piracy happened in small steps.

This tattoo should remind me that a moral north must be acknowledged, or you navigate at great risk. And when you find that moral north the deviations of culture, and the variations of law, make it hard to navigate. The points of the compass may be followed, but even your own ideals will lead you astray if you do not take the relative bearing of where you are and then calculate true north from there.

It seems that Captain Zetada, Jack, and L'il Jim all miscalculated. They didn't do the math among the waves of culture, law, and custom. Never mind the currents of opinion, or the bouyant tides of family. They all foundered. None of them took the time to calculate the true north based on the local measurements, deviations, and variations. But it was there.

For ourselves, we had a pretty good time watching it all go down, and we managed to avoid any problems. So I guess we found it.

And after we found that true north in Nicaragua we left, as sailors eventually do.

We sailed to Costa Rica, where we met gold miners, and we discovered people that had not even noticed they had a compass. Gingo eco-tourists and expats that were murdered for it.

Next: Gold Miners and Eco-Tourists, and more piracy.