El Chubascito!

Some luxuries should not be excessively enjoyed. These are the most extreme luxuries, already over-balanced, already over-ripe, such as civet distilled from ambergris, or the bitters of hyssop and melissa, pipe tobacco from Kentucky, or coffee that has been pressed out via ancient alembics that are sometimes used in coffee shops of Turkey. These things can make you sick, fast, but they are great pleasures. Shisha in Iraq cannot be over-indulged in, as it creates a unique nauseau that can take weeks to dissipate, and Xbox games when played straight, with only time to sleep, for more than a week turn tasteless and make the mind numb with the haze of virtual car dust and bullets. Laziness seeps into the mind in the seeds of poppies, and surely one should not wake up too early (nor go to bed too late) too often or one loses friends and finds oneself surrounded only by ghosts, and this is surely a kind of luxury and a decadence, these wee hours, for we think so well and clearly, but we should not over-indulge in such listenings of the nocturne. After all, most vice is its own punishment, and that is part of what makes a poison delectable.

A similar luxury, that should not be excessively enjoyed, is visiting the heart of a storm at sea. There is curious happiness to be found at the center of a violent squall. But one must look with care, and not too long. After all such substances as heroin, cigarettes and alcohol do not care if you die from overdosing on them.

Nor, as we would soon find out, does salt water and wind.

27 September, 16:00

The day had been calm. We had motored through the flat silky waters dragging us a Rapalla Silver Mick (which never brought in the dorado or tuna we hoped), trolling the lure under the water that showed our wake as a broadening gash, for an easy mile, in that smooth surface behind us. The motor boiled and hummed and it was a slow saturated day full of dense air tinged with rainbows.

It is always calm before a storm, but this is impossible to notice on land where things are never really calm nor stormy.

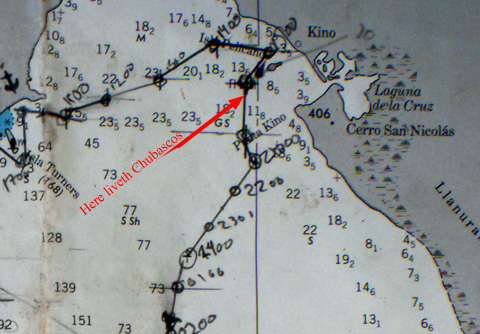

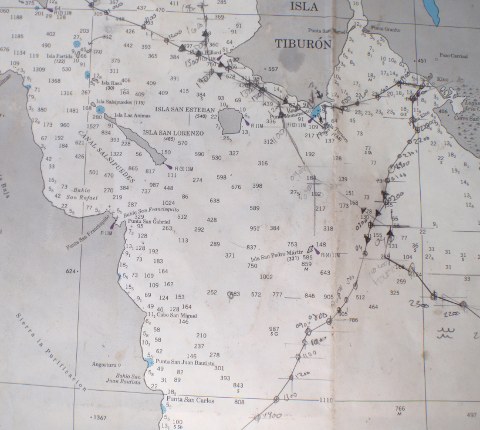

The squall started, or at least we first noticed it, at around 4pm. We had sailed south from the top of Isla Guardia, past Isla Tiburon, underneath that great walled beast, and had arrived near the little town of Kino with ambitions of anchoring and spending a few weeks there, working. Work had been building up and I had sold some paintings and Amelie had sold some articles and we needed to get them finished and sent off. Kino would serve as our home, or so we thought, for a few weeks.

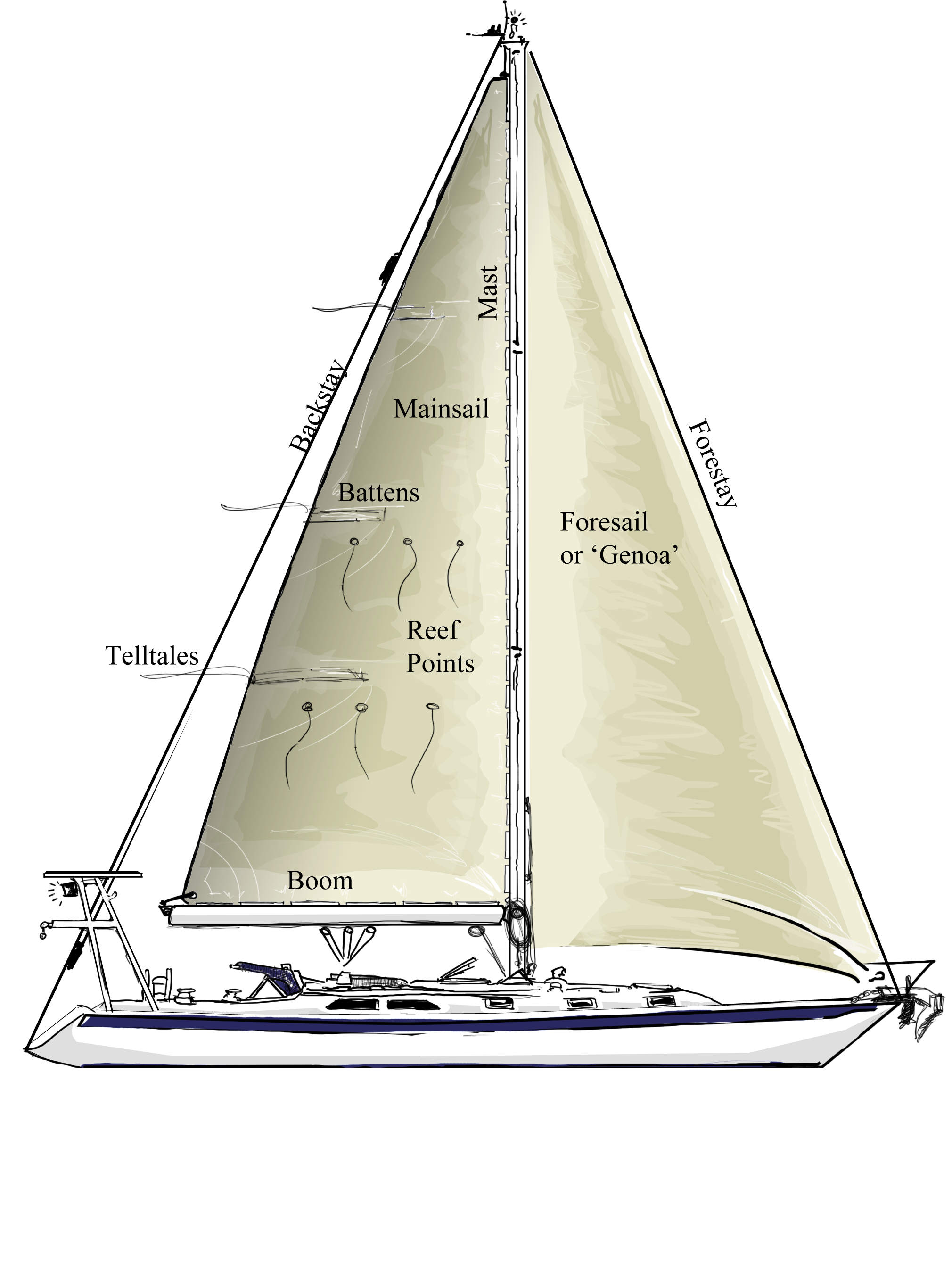

It was not to be for a number of reasons, none of which had to do with the storm, all of which we could see immediately, and so without so much as setting foot on dirt we turned the Goose around and headed south. We had spent two days at sea, but we turned around. Baja again. After all, we told ourselves, it was too hot on the mainland and after the clean austerity of the islands the last thing I was looking forward to was the petroleum film and motorized humming of land. Perhaps I just wanted to stay on the water for a couple days more, or perhaps the draft of the boat was too deep, or perhaps we were just tired, but in any case, we decided to turn the boat to west and south, and I unrolled the foresail and looked up as I did.

The sky that had been just a little cloudy all day had now become a large system, with a rather dark undertone, and it was inhaling. Once upon a time I heard a man on the radio call this "A Fluffy with a dark bottom." Perverted it did seem. A perverted explosion upwards, convection and condensation that was headed up, soon to come down again. It was well over the mainland, I told myself.

"That may be," I replied, "but the day has been smooth and sticky-calm."

"Sure," I told myself, "but these storms just sit over land and blow and fart and there's never a worry."

27 September, 18:00

At least it was sitting there and not following us out to sea.

It was starting to get dark and the clouds were lit a magnificent pink and yello

My barometer broke a few weeks ago, but I didn't need it to see a serious storm was getting lit up.

Underneath it flashed long fingers of lightning that seemed to tease land the way a child teases an ant colony.

I throttled up the motor a bit more and set our sights in the opposite direction. Whatever it was it was getting big.

27 September, 19:00

We had the motor on and both sails fully loaded. The winds were only about fifteen knots, but building, and coming from the south. We were flying west, fleeing from the lightning, which was the worst of my fears. The notion of being on a boat when it is struck by lightning (the notion alone) is enough to bring the motor roaring to life, the sails fully blown open, all systems on the Goose madly flapping, flying as fast as we can in the face of the storm. Lightning was my greatest fear, but I was not worried about it, as it seemed we had a good fifteen to twenty mile lead on the thing and surely, like any storm, it would sit there and mumble and grunt and throw some rain down and in the morning it would be gone and we would be more gone.

The wind was light. Not much, but noticeable after such a still day.

Behind us a fleet of fifty-four shrimpers vomited out of Laguna del Cruz, and all at once, and I reassured myself that they were going out to work not, as the Coast Guard does, leaving because a big storm is coming. After all, any experienced skipper would rather risk his boat in her natural element of the sea than risk her banging about on rocks and docks. At least that is what experienced skippers have told me, and I thought of this as we found ourselves surrounded by this horde of fifty-four killing vessels, dark as tanks and growling like dogs, a kind of mongrol army made out of rusty chain and patched nets. They were travelling west, and they were moving at twice our speed. Nah, I thought, They're just going out to work because it is night, like the calamari fishermen.

They drove past us and I looked behind.

I heard nothing on the radio. There was no discussion among them. I was still watching the lightning when we started to notice that the cloud was shaping into something that looked oddly like a huge mouth. It looked like some Sauron The Dark Lord was yawning, waking up after a good day's sleep in Mordor.

We were double-reefed, so the surface of sail was reduced to less than half what it would normally be. In that we would be on-time.

The sun set and with it rose a great blackness in the sky.

27 September, 19:10

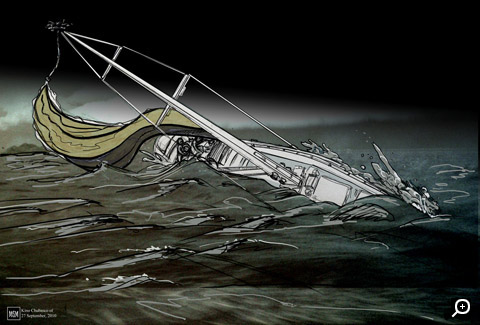

The thing lept from land to sea. It flew as if thrown, and sprang out over the water at more than ten times our speed. There was nothing we could do but look up as it engulfed us. The wind jacked from a pleasant fifteen knots to well over forty in less time than it takes to fill your car with gas. We were like little mice.

The rain started, and I asked Amelie to put on her jacket, and I put on a shirt, and mentally made a check-list of all we had, and had done. And with one hand on the wheel and one hand free I wriggled into my harness and Amelie into hers, and her face seemed slightly contorted, her eyebrows crawling like odd worms over her familiar face.

The attack came as I looked at her face. It took about 4 seconds.

First the wind hit on one side, so I brought the nose of the boat up, then before I could complete that maneuvre the wind had switched again, hitting us on the other side, hard, and laying us hard to starboard, a good sixty degrees, and the wind increased more in a massive gust, and I looked down and saw that we were in fifty knots of wind. I yelled to Amelie to hang on, but only some of it I could, myself, hear.

She grabbed.

We heeled hard and water came in over the gunwales, over, even, our winches, and I was pulling hard on the wheel, to bring us back to port, as the cockpit filled up around and cold water floooed up to our knees and suddenly Amelie and I both had thoughts of our little house being at the bottom of the sea, and with it all of our computers and clothes and other items that we did not want to be tossed into the sea.

I leaned hard on the wheel and brought the boat back up into the wind. Boats do this on their own in light winds, but if the winds are strong, or in a peculiar direction relative to a sail plan, a boat can be pinned and held in a suicidal tack, just as one can run frightened horses off a cliff.

Amelie went downstairs to look for water.

Happy to have fascinated myself and spent afternoons cleaning the scuppers the water left the cockpit faster than the fear left my chest.

The ship plunged downwards and then a shock ran through her, as if she had hit something solid, then she lifted again for the next wave.

Amelie's face re-appeared at the gangway.

She screamed something, and I could tell that, thanks to the good design of the ship, no water had entered.

I didn't know how much worse it would get, but water entering the cockpit, coming well over the combing, was surely an abuse of the rigging, deck, and a fine means of capsizing the boat. Amelie climbed back into the cockpit.

"We need to drop the sail, and we need to throw a sea anchor!" I shouted into Amelie's ear.

I looked at her and she nodded, and I heard her scream some words back and in them was the word "BUCKET" and "SAIL."

That was when the second attack happened. As soon as we had the Goose back up, or perhaps it was the strain of bringing her up into the wind, the sail exploded, and the luff of the sail, where it connects with the mast, broke loose and it filled up in a great round unhealthy shape. All I could hear was the wind even though the canvas normally pops as loud as a cannon, and I gave the wheel to Amelie and I scrambled forward onto the lurching deck to collect what was left of our flapping sail.

From that moment, with a bit of elevation to see, the water looked as if it had been scrubbed. Below us, streaks of powder-white water lept from the crests of the grey waves, their tops broken off by the same winds that had made them. Above us, the dark ragged mass of clouds sagged low, straining in a sinister way to get closer so as to flick us with those thin white fingers of lightning. And next to us, between the sea and the sky, bounced the fifty fishing boats their red and green and white lights on. In a flash of lightning I could make out their prows, pointed stubbornly into the sky, and upon their craggy decks could be seen the outlines of men, hunched forward, arms outspread, as if looking for some little thing they had dropped on-deck.

Then it went dark, the night quivered for a moment, and then the real thing let loose.

The wind screamed furious, and if it was fifty knots before it was harder now, and the rigging howled a low song of horror and dread as the boat helplessly was punched by one wave and then another. She was punched and then looted, and anything that was not tied tight to the deck, lashed firm to the rigging, would have been stolen by that wailing wind. I saw only some shreds of canvas leap from the Goose, and I gave Amelie the wheel.

Holding onto the boom with one arm I threw a rope around it with my other then clipped my harness to it. Under the glare of my headlamp I gathered the sail up in horrible bundles and armfulls, not folding it and caring for it as I have trained myself to do, but just grabbing huge armfuls, and lashing them to the boom with a rope, then being slammed in the ribs by the boom, then lashing more of our poor broken wing to the boom, then nearly falling from the deck, held only by the harness, which was more than fine and better than taking a bruising to the ribs.

Rain was lashing everything, horizontally, and I paused to look back at Amelie, at the wheel. She had her hood pulled around her ears. She steered the boat under motor power, her eyes trained on the water and the boats that were now within a stone's throw. In their steaming lights, from the little masts and working armatures, we could see the rain in long streaks.

Taking no inventory of the sail, I bound it fast, then got another rope and bound it again, imagining winds twice these could come. I climbed back into the cockpit.

We had been too slow. The sail should have come down faster. Something, also, gave. A double-reefed sail should be ok in fifty knots. But the investigation would come later.

"SEA ANCHOR! GOT MORE IDEAS!?" I shouted.

"BUCKET OR SAIL!" was her reply and I was thinking the same thing. The buckets would do some good, but I didn't have as much confidence in them.

I hauled out the spinnaker, which was crammed into a large canvas bag, and made my slow way to the bow of the boat. Now with the sails down our concern would be to keep the nose of the boat upwind, so that waves could not come over our transom and into the boat. She was designed to take waves on the nose, so by dropping something that held her nose upwind, the waves would just break across our bow, and we could wait it out. There would be no hoving-to, only waiting among our fifty murderous fishermen buddies.

But as I was too late taking down the main, I was too late putting out the sea anchor.

The winds stopped. Just quit, as if that great Sauron from the East had gotten tired, like an infant that throws a temper-tantrum, then falls asleep.

From the front of the boat I looked back to make sure Amelie was ok.

She was taking pictures.

I sat there for twenty minutes, breathing, as the wind and waves slowly decreased.

All misery eventually ends. Storms cannot continue forever.

Sailors and fishermen, the pleasure-cruise tourists and the heavy-metal captains, have never found the dangers of the sea reason enough to stay on land. The fears are more to be feared than the dangers, I have found, because the fear is what kills us, while dangers wake us and move our limbs. Fear makes us rigid, danger makes us supple.

But more than that, it might be that we go to sea to find something that comes with the storms. It might be that the lure of the adventure the sea offers is the very reason we step onto the boards and pull the topping lift. It is not that we seek the storms themselves, but surely there is something that accompanies them which is a joy.

It is also during a storm that the real personalities appear. For Amelie and myself, I discovered that we are action-driven and responsive, once there is a call of danger, but we were a bit slack and lazy before that. We had grown a bit fat, mentally, and after more than a month of smooth seas we had lost our ability to respond fast enough, nor early enough, and we nearly sank the Goose because of that. And we are of good nature while the shit hits the fan.

There is no danger in a storm, really. It is the spirit of the crew that makes things dangerous. Even if I were struggling to hold my nose above cold water and slowly sank lower, even if i could manage one sincere laugh in the face of the water god that pushed my face under, my death would be my victory. And I can see that we share that laughing spirit, the two of us, and so the sea offers no true danger.

But it does offer great inconvenience. And maybe even that is not so bad. After all, what is better for physical and mental health than inconvenience?

So we were fine, and during the night and during all the next day we crossed the sea, under only the power of our foresail and our motor, and we discussed these things and we made a list of what we would do, should we run into another storm.

And as we did so, unknown to us, another storm was percolating, up ahead.

28 September, 16:00

By 4PM that next afternoon we were welcomed to the other side of the sea by the following sight:

The clouds had had a vomit-colored tint throughout the day and only when the sun got low did they strengthen and turn their natural grey, and puff up their chests, as if health was returning to their aqueous muscles. The Goose rolled and floundered on the becalmed sea, her motor groaning in rhythmic complaint to something we could not understand.

As for us, we were both ready as two Olympic sprinters at the starting line. We had recently-sharpened knives in our pockets and harnesses on, headlamps had fresh batteries and the Goose's lines had been tightly arranged, motor oil and coolant checked and topped-off, log entries done, and, in short, we were not to be mistreated a second time.

28 September, 18:00

I had anticipated that this storm, as the other, would spring from land to sea just after sunset, and so we had a race to shore. With a 65 pound CQR and plenty of heavy chain I was confident our little boat would hold with sixty or even seventy knots of wind, and I was also confident that, in a properly protected bay, we could find our way out if the anchor dragged. With Amelie and I, together, even a hundred knots I would eat.

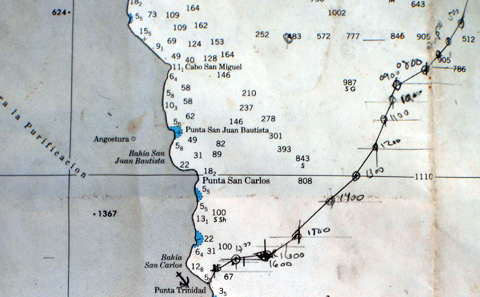

But still the race was on, and we saw as we came close to the Punta Trinidad anchorage that the storm, which was moving north, would best us.

28 September, 19:00

But it was just a little rainstorm. It blew over, sprinkled us with some rain, winds rose to 20 knots, and then it danced north.

After it passed it left the remnants of the sunset, kind of dual world of heavenly blues and oranges.

Anchorage

We anchored, easily, perfectly, to text-book specificity, and there, at our anchorage, and in our exhaustion, was where we found the pleasure of the storm. It was afterwards, in the peace, with the water smoothed out, that I realized the calm comes before, and after. We were wiped out from six days of straight sailing and the waves of the sea had emptied us of desire. Amelie took another photo, and in looking at it I was shocked at how, like any good poison, it had softened us a little, and given us some peace.

But, let it be noted, that some luxuries should not be excessively enjoyed.